Ciro worked up a version that doesn’t have such strong language, hopefully useful for spaces where that is more appropriate.

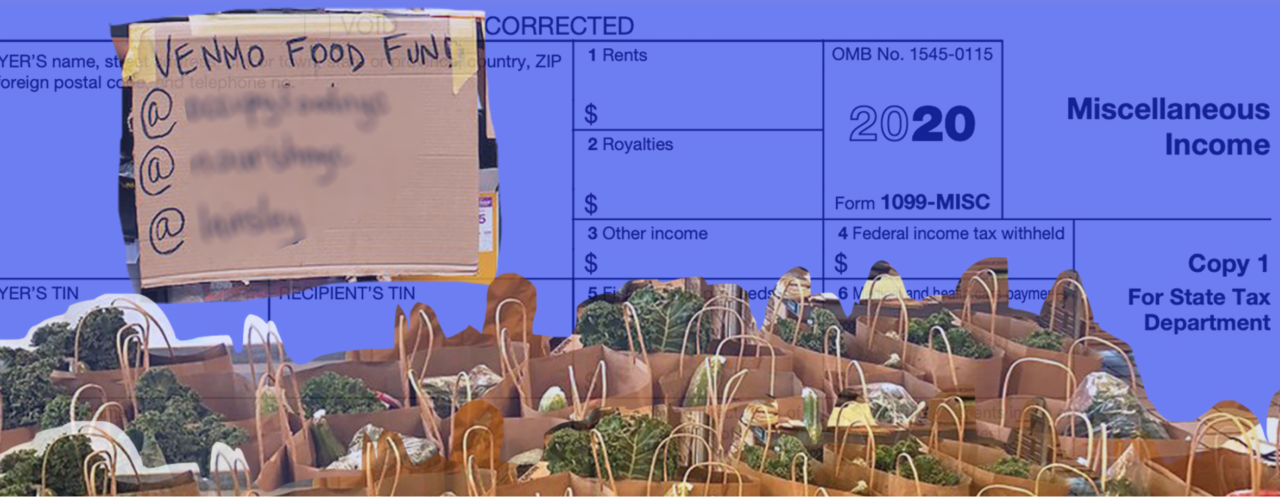

1099-K Forms and Taxes on Money for Mutual Aid Projects that Passes through a Member’s Payment Account

This post by Mike Haber is part of a series on Handling Money and Taxes. Mutual aid is rooted in community solidarity and movement organizing, but as activities grow in size and complexity, questions around tax and other legal issues can come up. In February 2021, Mike Haber and Dean Spade led a teach-in with BCRW addressing some of these issues (watch the video here). This series of posts on Big Door Brigade responds to specific questions people submitted after the webinar. Groups just starting to think about how to organize their mutual aid work may also want to check out this chart outlining some of the potential costs and benefits of different approaches to handling money in mutual aid groups.

My mutual aid group used my Venmo account to ask for contributions online and I got a 1099-K form showing that all of that money that the group used was income to me. Do I have to pay taxes on that?

A lot of mutual aid groups and other movement organizations that receive money through one member’s payment platform account (Venmo, PayPal, CashApp, etc.) have been worrying about what to do if and when a member receives a 1099-K form showing money for the group as taxable income just for that one member.

Starting next year (the 2022 taxes due in April 2023 for most people), this issue will be even more common: legal changes made in the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act mean that a lot more people are going to be in this position. Last month, the IRS, through its Taxpayer Advocate Service, finally gave some initial advice on what the IRS expects someone to do who receives a 1099-K form that incorrectly lists money that should not be counted as income.

First of all, if you get a 1099-K form, you probably shouldn’t just ignore it: if you get the form (or even if you don’t, but it was sent to you by the platform at the address they have on file for you), the IRS also gets the form, and they will be expecting you to pay taxes on the money reported on it. Just ignoring it could mean an audit or worse.

But is that money actually income that should be taxed? Maybe not.

Under the Internal Revenue Code, all income, regardless of its source, is taxable unless there is an exception. One important exception is for gifts, which the Supreme Court has defined as things given with “detached and disinterested generosity . . . out of affection, respect, admiration, charity, or like impulses.” In short, the Supreme Court says, “the most critical consideration . . . is the transferor’s ‘intention’.” When people send money to you to support your mutual aid group with an intent that meets this standard, it should not be taxable income–but not all payment platforms do a great job of explaining this to people who give you money, and, even if they did, someone might make a mistake in what boxes they check off on a payment platform app.

What the IRS’s Taxpayer Advocate Service has made clear is that the IRS expects taxpayers to sort out any errors on their 1099-Ks with their payment platforms, and will not offer a way for taxpayers to try to tell their story to the IRS, saying that “mistakes may happen” and that if a gift is wrongly reported on a 1099-K, “you will have to contact the payment app company to request they send a correction to the IRS. This could be time consuming.” It is also a good idea to keep any records that show money given to you through your payment platform meets this gift standard in order to make your case to that platform.

For more details on this, I have a piece that lays out this legal analysis in a bit more detail, and gives some tips for groups first considering different platforms.

New Legal Resource for Community Fridges

There’s a new legal Q&A guide for community fridges out now. You can submit any community fridge-related legal questions through this form, and a small team of lawyers will do their best to answer them.

This new resource is being supported by lawyers from the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, the Hofstra Law School Community and Economic Development Clinic, the Sustainable Economies Law Center, and the UCLA Food Law and Policy Clinic.

New Video about the History of Mutual Aid in the US

Video about Mutual Aid Inside Prisons

Don’t miss this video of a very useful conversation about mutual aid work that prisoners have done and are doing to support each other surviving inside prisons.

Two Questions on Fiscal Sponsorship and Mutual Aid

This post by Mike Haber is part of a series on Handling Money and Taxes. Mutual aid is rooted in community solidarity and movement organizing, but as activities grow in size and complexity, questions around tax and other legal issues can come up. In February 2021, Mike Haber and Dean Spade led a teach-in with BCRW addressing some of these issues (watch the video here). This series of posts on Big Door Brigade responds to specific questions people submitted after the webinar. Groups just starting to think about how to organize their mutual aid work may also want to check out this chart outlining some of the potential costs and benefits of different approaches to handling money in mutual aid groups.

If my group is a 501(c)(3) and acts as a fiscal sponsor, do the mutual aid groups we give money to need to pay taxes on it?

Generally speaking, no—those groups do not have to pay taxes on that money. Fiscal sponsorship allows unincorporated groups and groups that are incorporated but not tax exempt to avoid having to pay taxes on the funds that pass through your 501(c)(3).

Fiscal sponsorship is common in the non-profit sector, but the term does not have a precise legal definition and can describe a few different types of relationships between a group with tax exemption like yours (the “fiscal sponsor”) and any other group that agrees to comply with the rules imposed by the fiscal sponsor in a contract (usually called a “fiscal sponsorship agreement”). In that contract, the fiscal sponsor agrees to receive money on behalf of the project, which allows the project to take advantage of the sponsor’s tax-exempt status. Fiscal sponsors sometimes also provide some amount of support in bookkeeping and legal compliance. Depending on the kinds of services provided, fiscal sponsors charge different amounts for their services.

If you are interested in some of the different ways fiscal sponsorship can be done, Gregory Colvin and Stephanie Petit have a whole book on the subject. That may be more detail than you need, and Colvin has a good summary of his analysis of the different types of fiscal sponsorships here.

As a fiscal sponsor, your organization has its own tax-exempt purposes and compliance issues to monitor, and you are responsible for exercising some level of control over how the money passing through your bank account gets spent. Fiscal sponsorship contracts generally require the projects they sponsor to adhere to the obligations and requirements of 501(c)(3) status as part of that oversight. If money passing through your organization is used for non-501(c)(3) purposes, like election-related political activities, or to make a private profit for some individual, your organization risks consequences that could include losing your own 501(c)(3) status and owing taxes.

How can we reconcile the co-optation of mutual aid projects by fiscal sponsors, who may end up dampening efforts that were originally intended?

Fiscal sponsors can act in all sorts of ways toward the projects they sponsor. Some are demanding, some are fairly flexible and accommodating. Very few are fast, but some are unbearably slow. Many fiscal sponsors do not really understand the political project of mutual aid or have any sort of commitment to social change—but a few are real allies. Chances are, the bigger and more easily Googled the fiscal sponsor, the less aligned they will be with your mutual aid group.

Fiscal sponsorship can be a useful short-term tool for many groups. However, even well-intentioned fiscal sponsors can easily get snared by the non-profit industrial complex, and they end up prioritizing perfect legal compliance with the rules on tax exempt organizations above all else.

Finding a fiscal sponsor that is in political alignment with your mutual aid group can be a significant challenge, and many find it ultimately impossible. The alternative of starting your own tax-exempt organization is a bit of an undertaking, but it does give your group more complete control over the ultimate decision—in a given situation, do you want to comply with exempt-organization tax law or risk the consequences of taking an action that violates the law for some higher purpose?

Giving Small Rewards to Your Mutual Aid Group’s Donors

This post by Mike Haber is part of a series on Handling Money and Taxes. Mutual aid is rooted in community solidarity and movement organizing, but as activities grow in size and complexity, questions around tax and other legal issues can come up. In February 2021, Mike Haber and Dean Spade led a teach-in with BCRW addressing some of these issues (watch the video here). This series of posts on Big Door Brigade responds to specific questions people submitted after the webinar. Groups just starting to think about how to organize their mutual aid work may also want to check out this chart outlining some of the potential costs and benefits of different approaches to handling money in mutual aid groups.

What if donors to our mutual aid group are getting a small reward for a certain donation level, like if they get a sticker, mug, or t-shirt if they give $25 or $50?

We’ve probably all seen this in different contexts—both on crowdfunding websites (this is called “rewards-based crowdfunding”), and when a non-profit sends a small item as a thank you for a donation. To understand the legal issues that can come up for mutual aid groups doing this, consider these two examples:

- Example 1 Your mutual aid group offers a coffee mug with your logo on it that costs you $8 to anyone who makes a $10 donation to your project.

- Example 2 Your mutual aid group offers that same mug to anyone who makes a $200 donation to your project.

Mutual Aid Groups with Tax Exemption

For mutual aid groups that have tax exemption (like 501(c)(3) status) or a tax-exempt fiscal sponsor, Example 2 is clearly fine. You would generally record the amount of the donation as the total donation minus the fair market value of the goods or services provided, so if the mug is worth $10, you would record the contribution as a $190 donation. Depending on the amount of the donation, a written acknowledgement of the contribution might be required.

In Example 1, however, because the amount of the donation is close to the fair market value of the mug, that revenue could potentially be taxed as Unrelated Business Income—but only if your group “regularly carries on” the activity of selling mugs for $8 and only if your group has paid workers involved in the transaction. If, like many mutual aid groups, you use only volunteers, the revenue would be exempt from Unrelated Business Income Tax and would be treated just like Example 2.

Mutual Aid Groups without Tax Exemption

For mutual aid groups that are not tax-exempt and do not have a fiscal sponsor, the analysis is different.

Example 1 sounds a lot like an ordinary business transaction, and the IRS is likely to see it that way. If you are simply selling goods for a profit (no matter the important purposes you are using those profits for after you get them), (a) those transactions may be subject to state sales tax, and (b) your mutual aid group may have to pay income tax to the IRS. This would not be a gift, because the “reward” has a value comparable to the amount of the contribution. U.S. v. American Bar Endowment, 477 U.S. 105 (1986).

Example 2 is more clearly a thank you or an incentive. No one is likely to think that an ordinary coffee mug is worth $200, which means that the donor was giving your group that money for other reasons. If the donor was giving your group money out of “detached and disinterested generosity,” like out of “affection, respect, admiration, charity or like impulses,” it may meet the IRS standard for a gift and therefore could be excluded from your gross income. Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278 (1960). This should be true both for groups that keep their money in one individual member’s bank account and groups that keep their money in a bank account that belongs to the group as a whole.

Some people argue that in this situation, a group should be able to divide the amount given into taxable income ($10 for the mug, a regular business transaction) and non-taxable gift income ($190 as a gift), the way 501(c)(3) non-profits do. By extension, if your reward is something you also give out for free—like if you have a sticker with your mutual aid project’s name on it that you give out for free when you have events in person, but that you also mail to people who donate online—perhaps the entire donation should be considered a gift. That seems to me to be the most consistent interpretation of the tax code.

In general, the IRS has not been particularly clear about how it treats activities that might be considered rewards-based crowdfunding, and this is an area where you may want to be careful if you are giving out rewards that are worth more than a minimal amount. The IRS’s official position, unhelpfully, is that “the income tax consequences to a taxpayer of a crowdfunding effort depend on all the facts and circumstances surrounding that effort.”

Teach In: Handling Money for Mutual Aid Groups

On February 9, the Barnard Center for Research on Women is hosting a teach-in where Mike Haber, author of this useful guide for mutual aid groups about legal issues, will be sharing info about dealing with money and taxes for mutual aid groups. Many groups collected a lot of money last year and distributed it or bought supplied, food, tents and other survival items and distributed those. Now, some of those groups will be facing the problem of a tax bill for a member who used their Venmo or Paypal account to receive the money. Mike will be talking about these issues and more. We also made a handout for the event that might be useful, about how mutual aid groups can handle money. It looks at pros and cons of various approaches.

Project South Report on COVID Testing and Mutual Aid in the South

Check out this new report from Project South about the mutual aid work they are doing, providing free COVID testing. The report also looks at histories of radical mutual aid in the South that are so important for us to be learning from right now.

Handy Guide for Legal Issues Facing Mutual Aid Groups

Check out this handy guide that looks at the kinds of things mutual aid groups might get sued about or have tax problems about and offers clear answers to common questions.