This post by Mike Haber is part of a series on Handling Money and Taxes. Mutual aid is rooted in community solidarity and movement organizing, but as activities grow in size and complexity, questions around tax and other legal issues can come up. In February 2021, Mike Haber and Dean Spade led a teach-in with BCRW addressing some of these issues (watch the video here). This series of posts on Big Door Brigade responds to specific questions people submitted after the webinar. Groups just starting to think about how to organize their mutual aid work may also want to check out this chart outlining some of the potential costs and benefits of different approaches to handling money in mutual aid groups.

If my group is a 501(c)(3) and acts as a fiscal sponsor, do the mutual aid groups we give money to need to pay taxes on it?

Generally speaking, no—those groups do not have to pay taxes on that money. Fiscal sponsorship allows unincorporated groups and groups that are incorporated but not tax exempt to avoid having to pay taxes on the funds that pass through your 501(c)(3).

Fiscal sponsorship is common in the non-profit sector, but the term does not have a precise legal definition and can describe a few different types of relationships between a group with tax exemption like yours (the “fiscal sponsor”) and any other group that agrees to comply with the rules imposed by the fiscal sponsor in a contract (usually called a “fiscal sponsorship agreement”). In that contract, the fiscal sponsor agrees to receive money on behalf of the project, which allows the project to take advantage of the sponsor’s tax-exempt status. Fiscal sponsors sometimes also provide some amount of support in bookkeeping and legal compliance. Depending on the kinds of services provided, fiscal sponsors charge different amounts for their services.

If you are interested in some of the different ways fiscal sponsorship can be done, Gregory Colvin and Stephanie Petit have a whole book on the subject. That may be more detail than you need, and Colvin has a good summary of his analysis of the different types of fiscal sponsorships here.

As a fiscal sponsor, your organization has its own tax-exempt purposes and compliance issues to monitor, and you are responsible for exercising some level of control over how the money passing through your bank account gets spent. Fiscal sponsorship contracts generally require the projects they sponsor to adhere to the obligations and requirements of 501(c)(3) status as part of that oversight. If money passing through your organization is used for non-501(c)(3) purposes, like election-related political activities, or to make a private profit for some individual, your organization risks consequences that could include losing your own 501(c)(3) status and owing taxes.

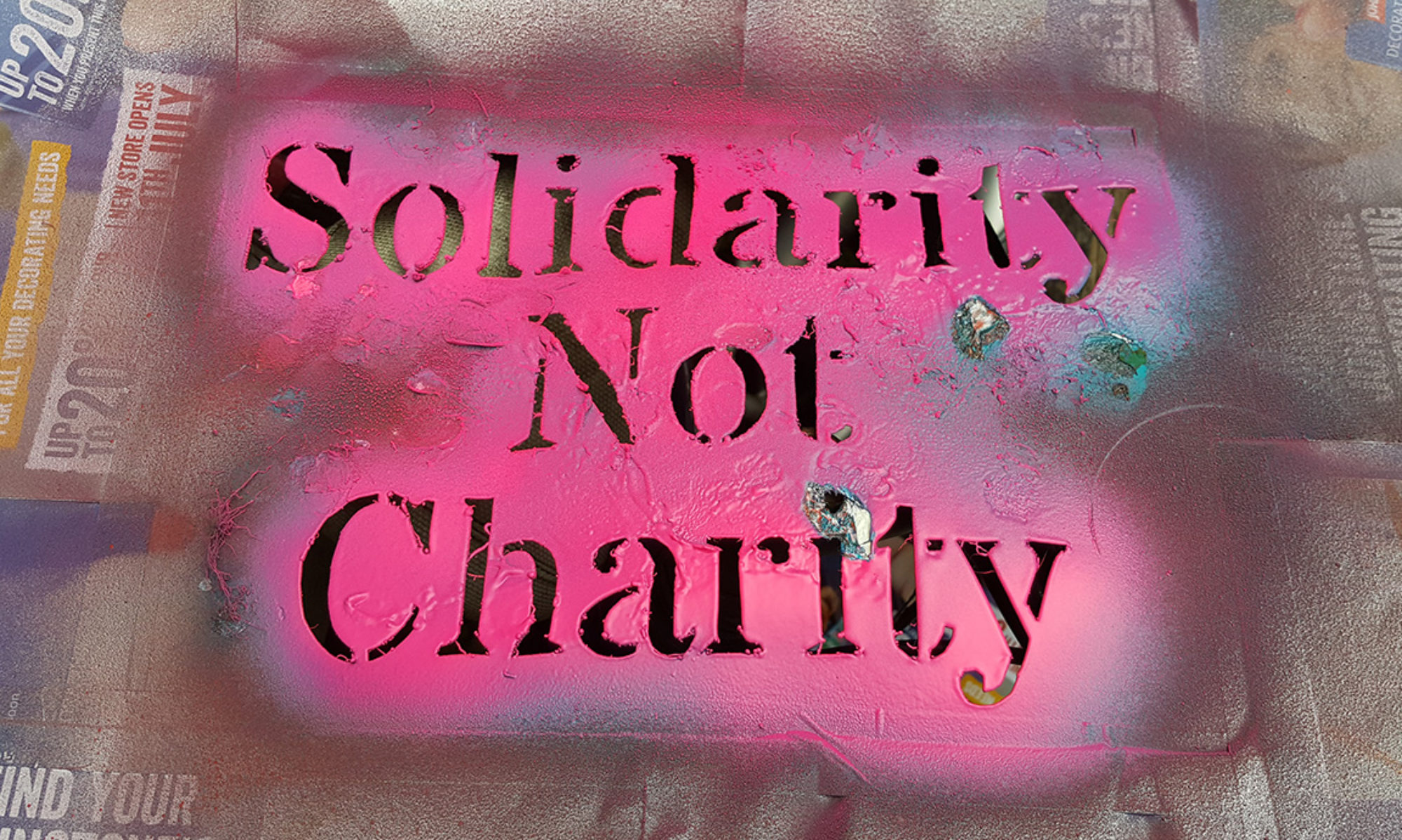

How can we reconcile the co-optation of mutual aid projects by fiscal sponsors, who may end up dampening efforts that were originally intended?

Fiscal sponsors can act in all sorts of ways toward the projects they sponsor. Some are demanding, some are fairly flexible and accommodating. Very few are fast, but some are unbearably slow. Many fiscal sponsors do not really understand the political project of mutual aid or have any sort of commitment to social change—but a few are real allies. Chances are, the bigger and more easily Googled the fiscal sponsor, the less aligned they will be with your mutual aid group.

Fiscal sponsorship can be a useful short-term tool for many groups. However, even well-intentioned fiscal sponsors can easily get snared by the non-profit industrial complex, and they end up prioritizing perfect legal compliance with the rules on tax exempt organizations above all else.

Finding a fiscal sponsor that is in political alignment with your mutual aid group can be a significant challenge, and many find it ultimately impossible. The alternative of starting your own tax-exempt organization is a bit of an undertaking, but it does give your group more complete control over the ultimate decision—in a given situation, do you want to comply with exempt-organization tax law or risk the consequences of taking an action that violates the law for some higher purpose?